interview

OLIVER LUNN

︎London/UK

november 06, 2019

november 06, 2019

Can you tell us a little bit about your background and where you grew up?

I grew up in a tiny village in southeast England. Compared to London, where I live now, it’s the middle of nowhere - fields, sheep, pub, not much else. My mum used to drive me to a multi-story car park in another town every weekend so I could skateboard. That’s basically how I spent my teens: skating in car parks and listening to music 24/7.

How did you start to explore art?

It initially came out of my interest in music. I loved noisy bands like Sonic Youth and would stare at their album artwork for hours. I liked covers that had a kind of scratchy aesthetic. Then when I went to art school at 16 I was obsessed with Basquiat, so I made paintings that crudely ripped him off. The work was angsty and loud, tossing heaps of colour on a canvas. But that all changed obviously when I met a girl, turned 18, discovered Cy Twombly’s work, and started listening to music like Magnetic Fields, Talk Talk, and Cocteau Twins. I was only really painting and drawing in those years though. The collage work came much later.

You studied Fine Art, didn’t you? What did art school do for you artistically, if anything?

The best thing about art school were the crits, where you’d have people standing around your work discussing it while you sweat in the corner. It could be brutal when people challenged your ideas and how well you translated them visually. But mostly it was positive. Understanding how your work is perceived, what works, what doesn’t. That definitely opened my eyes to new directions I could explore. Without art school I doubt my work would have developed in the same way, but it’s hard to know.

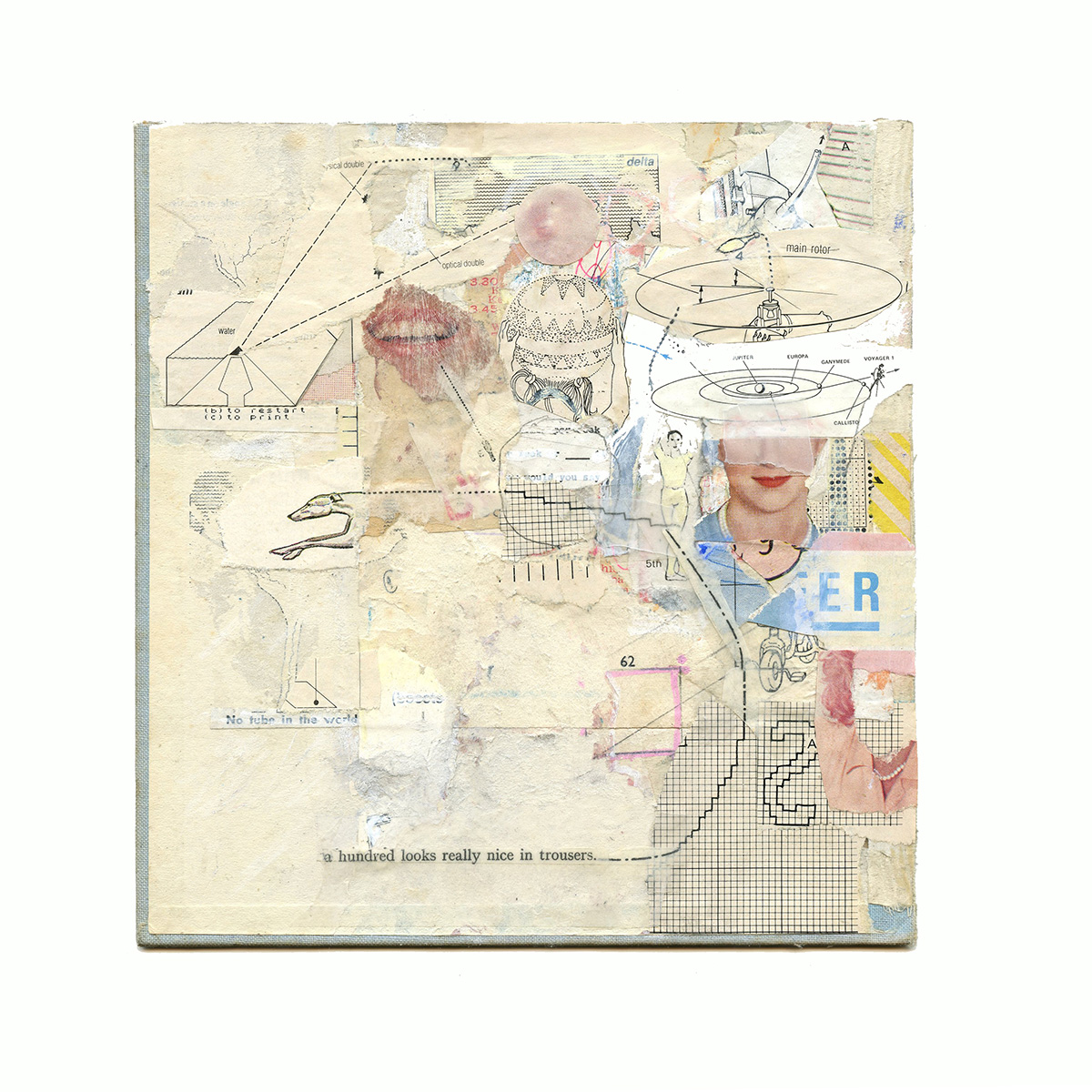

How would you describe your collages?

I guess I’d describe them as painterly. They’ve grown naturally from my older paintings and I approach them in a similar way. I’m interested in marks, mishaps, smudges, scribbles, used paper scraps. Some people have described them as sensitive or quiet, which I like. I’m not a very loud person so I’m happy if my work reflects something of my personality.

Would you like to talk a little about the process behind your collages? You work mostly analogue, correct?

Yeah, 100% analogue. I don’t think I could ever do digital, partly because I’m rubbish with Photoshop, partly because I work on my computer all day so making handmade works is an escape. I enjoy connecting physically with the surface of a piece, so my process is shaped by that. I scratch my nails over some bits, paint out bits I don’t like, Tip-Ex over small marks, muting unwanted colours. Thinking about it, I suppose it’s quite aggressive in a weird way. I make a lot of work by removal, erasing, masking. I’ll like something one minute, then hate it the next. It’s probably a self-conscious thing. I’ll hide things that feel too confident. I prefer things that feel tentative and nervous. I think confidence is overrated in art.

Can you describe your artistic process when you sit down to work on a piece?

I seem to have found a ritual that works. I mostly work in the evenings and I’ll put some music on, open a beer, and pull my lamp close over my workspace. I have an old shoebox that acts as a toolbox. It has everything I need: tapes, glues, pens, crayons, sandpaper. My source material is in another box that I empty out onto my desk. As for my process, I don’t have a set way of working. I’m always hoping to discover new ways of making marks, and you can only do that by upending any process you might have. That said, I can see I repeat myself visually. I’ll notice that I’ve joined two lines together from a diagram, or used arrows to pull a composition together. Honestly though, I try not to sit down and think: right, this is how I’m working tonight.

When you start a collage, do you know what you want it to look like in the end?

Never. And I never know when it’s finished! That’s the hardest part and I can drive myself crazy thinking about it. I usually know I’ve overworked a piece, and I have to live with the regret. I might not know what I want a piece to look like, but I’m usually working towards a feeling or mood. I always think of Brian Wilson’s songwriting process. When he had fragments of ideas that he’d mess around with on a piano, he’d call them ‘feels’. I love that description, because when we talk about process it can make everything seem so dry and emotionless, but it’s normally the opposite.

Which themes, ideas, or messages do you feel are particularly present or significant in your work?

One idea that seems to have stuck is the overlooked. I like the idea that my work might not look like much on first glance. It might just look like a piece of paper with a couple of marks, almost laughable. But if you slow down and look closer there are heaps of details hiding in there. That contrast is fun for me: that something looks minimal but might be teeming with quiet details. I hope someone can be surprised by that if they spend time with my work. A small part of it, too, is me rebelling against the noise of attention-grabbing art. Maybe it’s just me, but the majority of art I come across on Instagram feels like it’s a bit desperate for attention, visually speaking.

I am struck by the titles of many of your works, such as To the Tempo of Windscreen Wipers or The Brigade of Running Soft Boys. Do you feel titles are important to experiencing your work?

It’s funny, lots of people comment about the titles and they’re definitely another element of the work. They function in different ways. One is me trying to use humour as a way of offsetting something I find embarrassing or serious in my work. I get self-conscious about any perceived emotional elements in my work so the titles can help soften that. But then again, they’re not totally random. I constantly write notes on my phone – words I hear on the bus, snippets of conversation. Sometimes I like the way a word looks or sounds, especially when placed alongside other words. Then I think about that in relation to the mood of the piece. It’s basically another form of collage.

On your website you mention Cy Twombly as one of your influences. What aspect of his work had the biggest effect on your work?

I think his muted colours and scribbles are obviously an influence. I love going back to his work and noticing new things, marks that get lost under layers. I love that idea of the palimpsest, of something partially erased or written over, something secret and mysterious. His work also feels really sorrowful and poetic to me. It’s funny, I’ve never cried looking at a painting but seeing his work in person can definitely leave me breathless.

What are your sources for found images?

I tend to find stuff naturally. My mum gave me her mum’s old cookbook, which was handwritten on old paper and pretty much illegible. I never met her but it felt good cutting it up and touching the paper she’d written on. She’d probably be horrified. My mum was cool with it though. When my other gran died she had a load of old maps and knitting magazines that had scribbles and smudges on. I like materials that have a history, which I can dive into and become part of. I also find stuff in London that people throw out and leave outside their homes. And then obviously charity shops for extra bits.

Do you feel responsible for your images? How you dismantle figures, people, and rearrange their identities?

Not at all. I used to cut out figures cleanly, like a whole head or legs. But now I’m more interested in fragments, pieces whose sources you have to wonder about. For me, figures can distract sometimes. Viewers’ eyes are immediately drawn to them and often miss smaller details that are more interesting to me. It probably goes back to my interest in searching for a feeling in an abstract way.

How do you feel when you deconstruct a book?

I’ve actually had disagreements with my dad about this! He was trying to get rid of some old dusty books about the queen and obviously he saw my eyes widen. He knew what I was thinking. He looked at me like it would be a form of desecration, an act of vandalism. But in my defence, whenever I use books as material they tend to be broken or falling apart. I see it as giving them a new life. Plus, I’m not a huge fan of the queen.

I am a little horrified that you cut up your grandmother’s cookbook. I also admire the attitude that comes with it. Do you consider yourself a nostalgic person? Your work definitely has both, a vintage-y but also a decidedly modern feel.

Haha, obviously I wouldn’t have done it without my mum’s blessing. It probably sounds disrespectful to some people but it definitely didn’t feel that way. And that book was practically dust anyway. I do consider myself a nostalgic person. But when that relates to material I try to avoid using images that have become tropes in the collage world – 50s housewives, hoovers, things like that. There’s a retro trend in collage that doesn’t do much for me. It’s a bit on the nose, like a student’s comment on consumerism or something. There’s a few artists who use that imagery in interesting ways, but more often than not it’s the kind of stuff you see in coffee shops. And I know that sounds snobby!

What are you working on currently?

I’m experimenting with paint and mixed media more. I have some sample pots that I’m having fun with. I also mentioned how I can overwork pieces because I never know when they’re finished. So I’m trying to be more restrained and use space thoughtfully. Works by other artists that grab me make great use of space. So the stuff I’m working towards now is probably more minimal. But it feels like the possibilities are endless right now. The hardest thing is making choices, and the smallest decision about materials always feels like the biggest leap.

Do you make any other kind of art?

For a time I was taking photos. But honestly it was too expensive with all the film stock and tech gear. That’s what I love about collage: it’s pretty much free, you’re working with used materials that have often been thrown out. Anyone can have a go at it.

Oliver Lunn website

Oliver Lunn on Instagram

interview: Petra Zehner